Guarlford History Group

Guarlford in the 1920s and '30s for a "Newcomer" FamilyKeith Chester remembers life in Guarlford between WWI and WWII

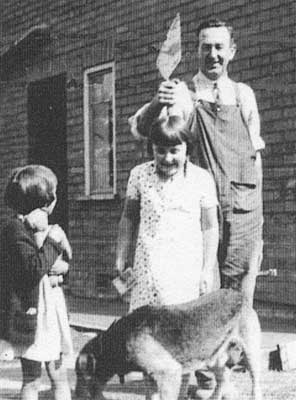

Living and making a living in the countryside must have been uncomfortable and difficult for everyone during that post-war and Depression period, but particularly for my father, Frank Chester, who came from urban Derbyshire where his father had a small Jacquard printing business associated with the lace industry. He was training to be a pharmacist before joining the army but was so traumatised by the horrors of the trenches at Passchendale and others that, like many other ex-army men, he yearned for the peace and tranquillity of the countryside. So, in 1920 he acquired The Homestead with its 7 acres of heavy clay pasture, a stable/cart shed and 2 pig sties, to set up a smallholding with no experience, little or no training and limited capital, but lots of determination. With the invaluable help of his assistant, local countryman Mr Bunn, he set about constructing a range of piggeries, poultry houses for about 300 free-range hens, and service sheds for feed storage, coal and workshop/incubator house. The 3 x 100 egg incubators, heated by paraffin, hatched his replacement stock. I well remember a childhood job of turning the eggs (marked X on one side and O on the other) daily with a wet finger to maintain humidity and to turn the embryo. There was so much for him to learn, and he must have had lots of help from indigenous Guarlford neighbours, but particularly Derrick Medcalf of New House Farm. Such a life brings its accidents and disasters, and Father was not spared his: soon after he got the business under way a large Lombardy poplar fell and demolished the service sheds, and a fire destroyed a shed with 100 chicks when the paraffin heater ignited the chaff litter. So he rebuilt them. With the poultry and pig business established he set about a new plum orchard, under-planted with blackcurrants. With the help of Mr Bunn he dug by hand the heavy clay of 1.5 acres of the field for the purpose. My earliest memories include earning my first pocket money picking blackcurrants with gypsy women, and watching the eventual grubbing-up of the bushes by a straining horse and chain. My mother had her own problems, not only supporting Father but also learning how to cope with a totally unfamiliar lifestyle. She came from a well-to-do family on the outskirts of London where others cooked and cleaned, with up- to-date facilities and education at boarding school in Darlington and finishing school in Switzerland, to a house largely devoid of any facilities. She had to learn quickly not only the usual skills of a wife and mother but how to cope with housekeeping with the very basic aids to living already mastered by most other Guarlford families, who had grown up with the discomforts of rural living in the '20s, unchanged for generations. The house she came to live in was a small Georgian dwelling which must have changed little since it was built before 1828, as it appears on the Foley map of that year, reproduced in "The Guarlford Scene". The wood and corrugated iron lean-to scullery may have been added later. Heating was by open fires in the kitchen and living room, augmented by portable oil heater. Lighting was by paraffin lamps and most cooking also by oil lamps, with saucepans, frying pan or oven rather precariously balanced on lamps in the scullery, augmented by toasting fork at the kitchen fire for toast, pikelets and, at Christmas, chestnuts. All not very convenient but the living flame of oil lights, the flickering shadows on the ceiling from the portable heater and the open fires gave the house a cosy glow in winter, I fondly remember. I can, however, find nothing to commend the water supply, sanitary fittings and drainage disposal arrangements. Water was supplied by an outside pump, and sullage was discharged through the hedge into the roadside ditch. The "sanitary convenience" was decidedly inconvenient, located as it was behind a lilac bush in the garden, and its spidery darkness was particularly uninviting in inclement winter weather. Poor Bunn had the weekly job of disposing of the bucket contents into the kitchen garden where it grew laudably organic vegetables for further recycling. The conveyance provided a fascinating breakfast time distraction for we children as it slip-slopped by the window.

Posh modern facilities arrived with Fred Tummey in 1934 when he built extensions and fitted "mod. cons.", most unfairly while we were away at school. Before the improvements the absence of electricity for washing machines, vacuum cleaners, electric irons, and no inside plumbing must have meant long arduous hours doing the household chores. Laundry was spread over two days: on Monday the washing was done in the brick, solid fuel copper, filled by buckets from the pump, and dried on an airer suspended from the kitchen ceiling. It would then be ready to iron on Tuesday, leaving the kitchen unfestooned. One thing my parents did both know something about was cars, such as they were. Father had driven and maintained lorries in France and Mother's war work was as a mechanic in a garage, to which she rode on her early motorbike. They acquired their first car, a Standard with a dicky seat, which they maintained with the help of Ranfords Garage in Barnards Green, and helped to justify the extravagance by introducing a taxi service in the village. Mother would take tourists into Wales when, no doubt, her repair experience would have been useful, at least for roadside puncture repair. Cars then had to be coaxed into life by carefully setting accelerator and ignition levers on the steering wheel and swinging the starting handle in the front. Stubborn engines were kept warm overnight in winter with an oil heater safeguarded by Davey lamp type construction. Steep hills, like Chance's Pitch on the Ledbury Road, had to be negotiated backwards by under-powered cars using the higher gearing. Even in the early '30's cars had no security: no ignition key and doors had no locks. If you could start it you could take it away - but no one did in those law-abiding days.

My Standard "Big 9" was made in 1931, acquired in clapped out state in 1946, laid to rest 1947. Canvas sides. The radiator did 5 miles to the gallon - of water (which had to be carried). Everything loose inside but, suitably re-arranged made a double bed for me and Gerald Smith, of Guarlford Court, on leave from army duties in Palestine, for our tour of the Wye Valley. To try to raise more income Father developed an earlier hobby, plate photography, and sold his picture postcards of the district, and Mother bred Airedale dogs. Neither venture, nor the taxi business, seem to have flourished. The dawn of "high tech." arrived with a wireless crystal set, I believe, when Paul was born in April 1922 and the telephone not long after. We did not have a private line but shared a party line with at least five others. We were 372Y4 and had to count four rings for calls to us. The Medcalfs and Lanes were also on 372. Curiously we still retained the number until we moved in 1963. There was no council refuse collection service so we used a dug hole for the few tins and glass we generated. As with other wastes disposal it must have been a problem for those with small gardens. The Medcalfs were so generous with their friendship and help for my newcomer parents and were very kind to me, who spent many days with Bill, playing in their farm buildings where, I remember, there was still a circular stone trough with another on a horizontal pole for crushing apples for cider-making, powered by a surely dizzy horse. When young Bill acquired his "Thelwell" pony called Mary, we learned to ride together, by trial and painful error, in the field opposite the football ground before the Listening Station arrived. I rode on the horse-drawn hay wagons at hay-making and watched threshing by steam engine, followed by the massacre of rats by dogs in the statutory wired enclosure round the base of the rick site at the end of the day. There were rabbits to be caught by pouncing on them as the corn reaper got to the last clump, and by Bill's ferrets and nets. I am sad that I cannot now share with him these memories of the farmers' world as it came to the end of a long unchanging era. Of course we boys were expected to help with the smallholding as soon as we were capable. We learned to use mower, sickle and scythe, and to feed, muck out and move pigs and poultry. (Why is it that hens are so dozy at night they will allow themselves to be carried upside down, 2 in each hand, without protest when other birds can migrate at night?) We learned to kill, pluck and draw chickens, and kill, skin and gut rabbits (though not to enjoy it) and how to move pigs when they don't want to go. A potentially fraught venture of a solo trip with a sow along the road to Heriots Farm to be served by their boar turned out uneventful however. She seemed to want to go. Entertainment and Recreation Nightlife in Guarlford for my parents in the '20s must have been limited and less than riotous. In fact until the Men's Club acquired the Malt House premises and later made the hall available for village gatherings, evenings must have been the Plough & Harrow pub for men and making and mending for women, or early to bed - or both. During the day I know only of my parents playing tennis at the Rectory and, I believe, the Cherry Orchard and Guarlford Court. Early memories of being taken to the Cherry Orchard include the Robathans' sulphur crested cockatoo, their so fashionable rotary summerhouse (to catch the sun) and being sent out to scare the birds from the cherries by pulling strings to set clanging the wonderful collections of anything and everything that would clang, hung from tree to tree. But how did children survive through the dark winter evenings without television? In our case, as with many, as young children we were packed off to our unheated bedrooms with a paraffin lamp straight after tea. When older there were board games, card games, jigsaws, and making something: knitting, rugs, fretwork, models, most destined for long-suffering adults as presents. Music was provided by the wireless and by the limited supply of short-play records on the horned wind-up gramophone. Occasionally we were encouraged to sing Victorian ballads and Negro spirituals with Father on the piano. Unsurprisingly there were no invitations to go public! During the day we children spent most of our time outdoors - and not only because "If you hang about in my kitchen you'll be given a job". We made our own entertainment outside. For Paul and me there was cricket, tennis with a Kumbak (tennis ball on elastic), and crazy golf. We created a wire netting cricket net and concocted a golf course with the help of guttering, piping and sunk cocoa tins. Bicycles, graduating from fairy cycles with solid tyres, were invaluable: expeditions to the Hills, the Old Hills, the rivers at Clevelode, the Rhydd and Twyning, and to tax poor Mrs Bullock at Guarlford Stores, who had to hobble painfully out to open up for us for bootlaces of liquorice or a penn'orth of gobstoppers. We cycled too to Dripshill Farm to play hide and seek with the Monkley children - until Paul and Doris didn't want to be found. They later moved to, I believe, the farm which is now the Malvern Show Ground, where poor Raymond became paralysed with polio. Paul and I learned to shoot, first target practice with an air rifle and later to shoot rabbits with a 12 bore kindly lent by Ron Smith to reduce the over-abundant supply in his fields opposite us. I first learned the joys of driving a golf ball in his field, though the "fairway" was not very fair. There was the usual rough grass and pats left by cows but also the field was curiously ridged and furrowed, presumably unchanged until WW2 since medieval times, as referred to in Appendix 1 in the Guarlford Story. At Clevelode we swam from the "beach" at the foot of the cliff reached through Mr Little's orchard, for which we paid a small fee. The complete absence of any facilities provided a different experience from the safe and sanitised Priory Park. We paddled in the Malvern sewage works brook at the beginning of Wood Street and the end of Penny Lane. It must have been reasonably well treated as it contained water voles and sticklebacks in a field further down.

The admirable countrywise Bunn also taught me how to catapult, make a whistle from a willow stick and how to cope with a bolting horse. The latter, surprisingly, was to prove useful when sister Barbara's pony bolted when we tried her in a milk float. He entertained me one day by climbing to the top of a tall elm with the help of climbing irons, which fascinated me and appeared (and were ignored) on my Christmas wish-Iist for many years. They were iron spikes clamped to the inside of each ankle to dig into a tree trunk or, more usually, a telegraph pole. The purpose of this exercise was the removal of the eggs from a crow's nest as they had been predating our chicks. I was glad to add them to my collection. Lying in bed listening to a nightingale through the open window, together with birds egg collecting, started my life-long enthusiasm for the wild life of the English countryside, and for birds in particular. I had then a better memory for their song, and it stuck. I was so fortunate that farmers in the '30s did not mind local boys and their dogs on their land, and the Victorian enthusiasm for, and ecologically accepted hobby of egg collecting (but only one!) still prevailed and, as with so many, turned me from "poacher to gamekeeper" in later years. I still have my grandfather's 19th Century bird and butterfly books and beautifully made egg-blowing equipment. Being good farming land, bird and flower diversity in Guarlford was limited, but I enjoyed drumming snipe and tumbling lapwings in the adjacent osier bed. Oh those joyful "peewit" calls! Most pasture fields had ponds dug long before in the retentive clay for the grazing cattle, and each pond seemed to have its resident moorhen family whose eggs some people found good to eat. The Atwood boys from a neighbouring cottage showed me how to reach the otherwise inaccessible nests over the water with a matchbox tray on the end of a long stick. The nightingale is rarely heard in Worcestershire now, I expect, but they were still about during World War Two. On a dark, drizzly otherwise silent summer night when I was alone "guarding" the Hills with the Home Guard near Hollybush Pass, I had the magical experience of a prolonged concert by a nightingale very close to me. Thank you, Home Guard, who also gave me the memory of a night under the stars (no tents) after shooting at the rifle range at West Malvern. We woke to dense fog but on a march to The Wyche we climbed into brilliant sunshine with the hillocks and hummocks of Herefordshire as so many islands rising through it. The War was not all doom and gloom. As to wild flowers, there were primroses and king cups in South Wood, sheets of bluebells and some windflowers in Dripshill and milkmaids in the damp hollows of the field opposite The Homestead. I wonder if there are still wild daffodils on the Hills above the Gullet Quarry? Christmas was so different then. It did not start with shopping, parties, lunches, cards and decorations many weeks before, leaving The Day a jaded anti-climax. For my family, when the day did dawn - well, well before dawn usually, with stockings in the dark, it was very special. Entry to the drawing room was strictly forbidden until morning chores, including feeding pets, pigs and poultry were completed. When we were allowed in, it was to see the decorations for the first time and we were stunned. Our parents had been very busy after we were in bed festooning the room heavily with paper chains, balloons which swayed gently suspended from the ceiling, and a Christmas tree decorated with baubles twinkling in the light of real-flame miniature candles. After tea there were indoor fireworks and cracker-type trinkets housed in a cardboard cottage: lights out, light the blue touch paper and ...boom! Trinkets all over the room. Can't think why we don't see them now! Christmas is the poorer without such magical ingredients, but safety-wise perhaps it's just as well. It is though, I am sure, the stuff of lasting memory, not just for me but typical of the way Christmas was celebrated by most families with several small children before the upheavals of the last War. After the home joys of Christmas Day, there were parties with others confined, as they were, to the short period of the Twelve Days of Christmas. There were games which had been played, until then for generations, if not centuries, such as Ring-a-Ring-a-Roses, Musical Chairs and Blind Man's Buff, but less well known were Spinning the Trencher (a wooden pre-china dish) and frog racing with home-made cardboard frogs jumped along strings. For larger gatherings games and dances included Oranges and Lemons, accompanied by an age-old ditty about City of London church bells, and Sir Roger de Coverley, presumably the country squire of the essayist Joseph Addison three centuries ago. Post puberty parties introduced exciting surely post-Victorian games of Sardines (squeezing into cupboards and under beds in the dark - with girls!) and Postman's Knock (kissing!), memorably at the Newsons' parties at The Rectory. I feel fortunate to have lived in Guarlford through my childhood years and experienced and seen a way of life largely unchanged for generations. I have watched such ancient crafts as demonstrated by Mr Cole the wheelwright fitting the iron tyre he had made to a cart wheel, heating it in an open fire and quickly shrinking it with buckets of water on land opposite Woodward's garage. The fascinating art and sparks of the traditional blacksmith I enjoyed at Mr Welling's smithy at The Heriots. On the farm hay was cut, tedded and carted by horses with some stored in the field in thatched ricks, giving opportunities for rides on the carts and gentle giant horses. Can young children of today, with their plethora of sophisticated indoor toys ever experience such thrills as Christmas past, riding a donkey up to the Beacon or flying in an early open-cockpit aeroplane with pioneer aviator Alan Cobham from Mill House Farm? Will they, nearly eighty years later, remember such adventures as steam train rides alone in the charge of the guard all the way to London? These were highlights of a childhood in Guarlford in which our parents could send us outdoors to find our own simple pleasures and healthy occupations in comparative safety to learn joy - and sometimes pain - from active experience. But was it really better? "What are those blue remembered hills, What spires, what farms are those? That is the Land of Lost Content, I see it shining plain, The happy highways where I went, And cannot come again." A.E. Housman

|