Guarlford History Group

Publications - The Guarlford StoryChapter 6 The Village SchoolPrefaceIn books and films the ideal village has a church, a public house, shop and school. Guarlford still has its church and two public houses, but no longer any shops and, importantly for the heart of a village, the school sadly disappeared many years ago. Significantly, there are numerous accounts of childhood and school in English literature, evocations of what are usually the most formative years of life for all of us. Childhood’s often intense experience characteristically includes moments and times, whether happy or painful, which are remembered with great vividness in adulthood many years later, as if they occurred only yesterday. Perhaps the popular novels of Dora Saint, ‘Miss Read’, still in print and to be found in most public libraries some fifty years after establishing themselves in the affections of readers, modestly but effectively convey in prose what is for many readers the essential appeal of remembered childhood days, albeit in an idealized village setting. ‘Fairacre’, the fictional place in which the narrative is set, itself conjures up a small, blessed plot of land, while the walls of the school reflect “summer light with honeyed mellowness”, just as memories of time spent at a village school are often bathed in such mellow light. First published in 1955, Miss Read’s Village School has become something of a modern classic and a touchstone of nostalgia for schooldays. Another minor classic of childhood and school days, Cider with Rosie, an autobiographical work by Laurie Lee, which was published four years after Village School, in 1959, was aptly summed up in a review by the novelist H E Bates as putting on record “the England we have traded for the petrol engine”, in this case the England of the immediate post-First World War years. Lee writes, “Our village school was poor and crowded, but in the end I relished it. It had a lively reek of steaming life: boys’ boots, girls’ hair, stoves and sweat, blue ink, white chalk, and shavings.” Guarlford National School

Figure 6.1 The Class of 1900.

In the early nineteenth century, because of growing concern about the educational standard of the population, there was throughout England a proliferation of private and church schools and in 1861 a Royal Commission recommended that local Boards of Education should be created and empowered to collect a ‘school rate’ and to build schools. No exact date has yet been discovered for the opening of Guarlford National School. However, a letter of March 4th 1946, about an architect’s inspection, refers to the school building having been “erected in 1867”, and some plans of the school and ‘School House’, now in the Records Office store in Gloucester, are signed “McCann and Everal March 1867”, (a George McCann built the Church in 1844). A resident has a Bible presented to her grandfather, George Lane of Woodbridge Farm, with the commendation that it was awarded on July 25th 1872 for “good conduct and regular attendance at Guarlford School”, and she also has a book presented in 1903 to her uncle, another George Lane, as an attendance prize. W E Forster’s Education Act of 1870 had marked the birth of a national system of education, while the Act also required the establishing of Elementary Schools nationwide to supplement those already in existence. School Boards could charge up to nine pence a week and had to guarantee that children aged five to thirteen years would attend: a School Attendance Officer was appointed to enforce this. Then came the 1891 ‘Free Education’ Act, when the Government took on the responsibility for providing education, which was compulsory for children aged five to ten years. The 1918 Education Act raised the compulsory school leaving age to fourteen. There are references in the Log Book to ‘aid grants’, the amount given being dependent on pupils passing certain tests. Between 1898 and 1901 Guarlford National School received on average twenty pounds per annum in aid grants. The Parish Council records also refer to the ‘Lloyds Charity’, the income of which was shared between Great Malvern and Guarlford. In 1896, Guarlford’s share was £4-12-9d (£4.64) “… of which one pound was for the education of poor children”; the members of the Parish Council decided that the education money should be passed to the School Manager. The BuildingsThe school and ‘School House’ stood between the Church and the Rectory, side-on to the road, and, when the ‘School House’ was sold after the school closure, the conveyance included a document regarding an 1843 deed of gift of land for the building of the Church and Rectory from Mr Edward Thomas Foley and the Vicar and Churchwardens of the Parish of Great Malvern. There were two separate playgrounds, one for the boys, and another for the girls and infants who entered the school at the front, via a cloakroom, which led into the main classroom with its high-pitched ceiling. This classroom measured 33ft by 18ft. The boys had a separate entrance and cloakroom at the back of the school, also leading into the main schoolroom, from which a door led into the smaller classroom (20ft by 10ft), which the plans show with a gallery, later removed. The 1867 plans also have drawings of the “girls’ and infants’ privies” and these, with those used by the boys, were just outside in the playground. Mr Kenneth Woolley, born in the ‘School House’ in 1925, remembers that at the school “… there was a pump in the girls’ toilets, from which Mr Clark, the caretaker’s husband, would fill a large header tank from the well, then open a valve to give the toilets a daily communal flush. The day’s ‘takings’ would then proceed past an inspection cover just inside the School gates – we were never able to discover the final destination. Progress was often blocked by tennis balls and other objects. Clearance was often part of the headmaster’s duty.” A flue for the stoves was built into an internal wall, and in 1903 concern was expressed about the lack of ventilation, as the windows had been made without any ‘hoppers’, that is, small opening windows for ventilation; but it was not until 19th August 1910 that there is a reference in the School Log to the great improvements in the school building after alterations to the windows had been made in the spring of the year.

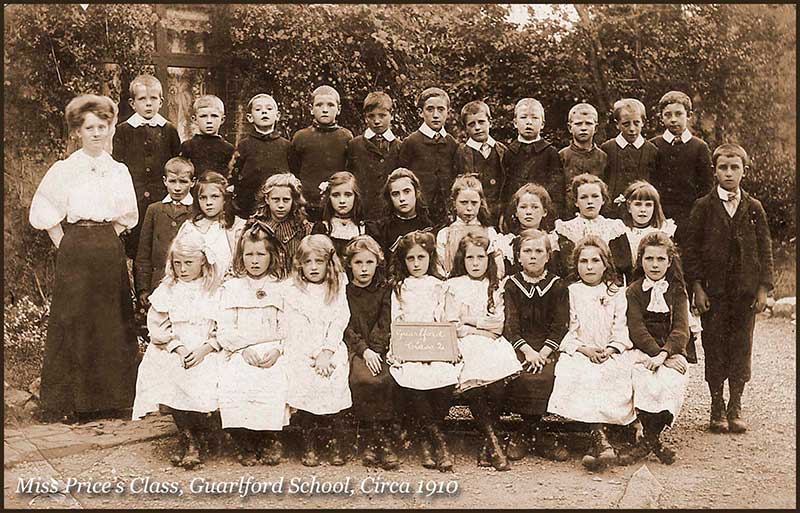

Figure 6.2 The School and School House. Thomas Hayes: a Pupil in Victoria’s ReignThere are few early written records about the school. The surviving School Log Book runs from 1900 to 1946, and there is also an exercise book from 1890 in existence belonging to Thomas Hayes of Clevelode, whose family were basketmakers. Thomas could only have been about twelve years of age (and so one of the older pupils); his book is remarkably neat with beautiful copperplate handwriting. Parsing sentences (analysing the structure and naming all the parts of speech), dictation, transcription and some composition work form the English syllabus. A composition from July 15th 1890 reads: “On Saturday I went to Worcester, first I went to the Museum, and I saw different kinds of birds, a child’s skull, a big tiger, Chinese shoe, monkeys, birds eggs, horse’s and cow’s skeleton, mammoth’s tusk, leopard, a young deer, thrushes nests and their eggs, skeletons of birds, snakes skin, ferrets and their young ones….. I went from the Museum to a coffee tavern and had my tea, then I went to the Cathedral while service was on, one boy sang by himself. I looked round and went back home by train.” In Mathematics young Thomas was tackling exercises in vulgar fractions, decimals, simple interest and various other problems, all sums clearly and neatly written. Geography consisted of drawing detailed maps of England and Wales, Scotland and an Ireland without any border across the country. Thomas wrote essays about these and also life in Canada. Any empty spaces on the pages are filled by handwriting practice, using quotations from poems and ‘wise sayings’. All this written in ink with remarkably few mistakes and blots! The Log BookThe only Log Book available is kept in the Worcester Records Office at the HIVE and covers the years 1900 to 1946. It begins with commencement of Mr A E Martin’s time as Headmaster, starting on February 5th 1900. The school consisted then of the two rooms and two classes, with seventy children in the ‘Mixed School’ and fifty in the ‘Infants Room’, where Mrs Martin was the teacher, together with an assistant. Joan Bradshaw’s mother, Miss Price, taught at the school before the First World War. The mixed class, taught by Mr Martin, had pupils from seven to thirteen and, later, fourteen years of age.

Figure 6.3 Miss Price and the Class of 1910.

Several times Inspectors state that the school should really have three teachers, and assistants of varying talent and attendance filled the gap. There are many references in the early part of the Log Book to the ‘migratory’ character of the pupils. This was presumably because agricultural workers often moved to find work as the seasons changed. In November 1908, the Headmaster notes that within seven weeks ten children had been admitted and nine had left. The classes may seem to be very large, but early Log Book entries point out the erratic attendance of the pupils, mainly because of bad weather but also because children stayed at home to help with work on the farm and in the house. Indeed, significantly, special notes are made of times when most of the pupils are actually present. Childhood illnesses were rife: for example, in January 1904, the school was closed for five weeks because of an outbreak of measles, and it is recorded that throughout the lifetime of the school snow and floods kept some children at home, especially the little ones. The ‘catchment area’ was large, and Alf Young of Hall Green recalled that, when he attended Guarlford School from 1928 onwards, the school also used to take its pupils not only from Guarlford village and Hall Green but also from Clevelode, Hangmans Lane on the road to Upton, and as far as Old Hills at Callow End. The necessity for the able-bodied of all ages to help with the Harvest was recognised and the summer holidays were adjusted accordingly, with two weeks in July and then the whole of September (for the hop-picking), something which continued well into the twentieth century. Even so, an HMI report in 1912 makes particular reference to the fact that there were still too many absences, which can easily be understood, given that even later in the century children were tempted to help in the fields instead of going to school. The highlight of the school year at that time was the summer outing, which would be to the Old Hills at Callow End, where the children had sports and a tea party. The journey was made in a harvest wagon belonging to Mr Bradshaw, who farmed at Guarlford Court Farm. Mrs Lil Gilroy was one of the large family of Morris children, eleven in all, who lived mostly at Clevelode. Mrs Gilroy went to Guarlford School in 1917 at the age of ten and remembers that every year at Christmas there was a School Concert; she recalls singing ‘Three Old Maids of Lee’, with friends Amy and Annie. Evidently, in freezing weather, Mr Martin used to throw water down to create for the children a frozen slide running from the playground into the lane, and every time the Hunt met the children were taken to the corner by the church to see the horses and hounds. The CurriculumDuring Mr Martin’s time as Headmaster, the subjects studied included English (much Grammar), Arithmetic, Religion, History, Geography, Needlework, Drawing and Singing. Intriguingly, in 1908, an Inspector suggested that in the Infants class the practice of reading sentences backwards should be abolished. Behaviour is generally noted as good, but, characteristic of reports on many rural schools in those early years, country children could be very reserved, so oral work was difficult. There are references to ‘Drill’, but most surprising is the fact that on March 19th 1901 chemicals and apparatus for Science lessons were received, and Science was taught to the whole school, including “lessons illustrating the properties of oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen and chlorine; the chemical character and constituents of pure air, and the nature of the impurities sometimes found in it.” Sadly, there is in the Log no record of how the pupils responded.

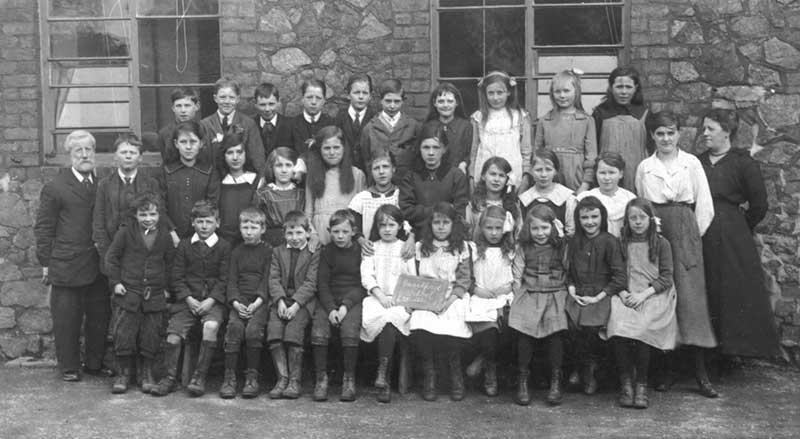

Figure 6.4 Mr and Mrs Martin and the Class of 1920.

Alf Young said that his father and uncle, who attended Guarlford School in the early decades of the century, told him that, during the First World War, boys could leave school at about the age of thirteen, because they were needed to work in place of the men who had gone to war. They were interviewed by Miss Severn Borrows of the Malvern District Committee, and she decided whether they had had enough education. The School Log Book has an entry for April 1915, which says that, because of a shortage of farm workers, all the boys over twelve years of age, except one, had been given leave to go to work. In June 1915, the authorities even allowed boys under the school leaving age to work with the harvest, and the headmaster found it difficult to make some of them return… Mr Woolley, Headmaster 1923 - 1941The Log Book records that on April 16th 1923 Mr Clarence William Woolley became Headmaster of the School, and it is from pupils of his era that the most vivid memories come. Mrs Phyl Bayliss shared her school life with Mrs Rene Sims (then Waters) from 1921 to 1930 and says, “I loved Guarlford School; I didn’t want to leave a bit!”, a sentiment echoed by many. Pictures of the schoolrooms are fresh in the minds of ex-pupils still in the village today, a common experience and one echoed in many literary accounts of schooldays. Particularly remembered in Guarlford’s case is the fact that at that time the big room was divided by a curtain about five feet in depth to create two classrooms. If you were in favour, you were allowed to draw the curtain for lessons after Roll Call and Prayers. There were large ‘tortoise’ stoves, one in each room. Some former pupils remember that the large room didn’t get warm until they were going home. Mrs Clark, the caretaker, lit the stoves on winter mornings. In Cider With Rosie, Laurie Lee describes the stove in his own village school: “It was made of cast-iron and had a noisy mouth which rattled coke and breathed out fumes. It was decorated by a tortoise labelled ‘Slow But Sure’, and in winter it turned red-hot”, a description which would have been familiar to many who attended Guarlford School, where at times the fumes from the stoves made the classrooms distinctly foggy, particularly before the ventilation was improved. Mr John Little remembers, in the late thirties, the chill being taken off bottles of milk by placing them on the stoves. Before the introduction of free school milk, Mr Woolley thought that children should have something at playtime to sustain them and he used to make ‘Horlicks’ for them, heating milk on the stove – the ‘Horlicks’ was mixed laboriously with a ‘plunger’ gadget. Mr Woolley was evidently a ‘kindly disciplinarian’ and is praised in Inspectors’ Reports for overcoming the country children’s natural reticence. He continued to teach the basic subjects soundly and to broaden his pupils’ experience: there are references in the Log Book to trips to the ‘Malvern Assembly Rooms’ and the ‘Picture House’ to see plays by Shakespeare, travel films and even Ben Hur in November 1927, together with other excursions. Ken Woolley remembers one such excursion, which was a conducted tour over the ex-German liner ‘Berengaria’ – he thinks in Southampton. Sam Beard says, “Over a period of time Mr Woolley firmly fixed life’s educational requirements and good manners into our largely unreceptive minds.” Miss Cope and Miss Cole, class teachers

Figure 6.5 Miss Cope and the Class of 1930. Back row L-R: 3rd Charles Bladder; 5th Sam Beard. Front row seated L-R: George Fisher; Joyce Clark and Ernie Clark far right.

The school became a three-teacher school for a time, with Mr Woolley as Headmaster and teaching (classes known as) Standards Five and Six (the Seniors aged eleven to fourteen). A Miss Lindsay has been mentioned as a teacher, but most people recall that in the 1930s Miss Cope, daughter of Police Inspector Cope of Upton, taught the Junior Class (Standards Three and Four), and Miss Cole, daughter of the wheelwright in Chance Lane, reigned supreme in the Infants Class (Standards One and Two). As Pamela Fairhurst (nee Newson) recalls: “My memories really start at the Village School next door to the Rectory; one small room was my world – the Infants room – presided over by one of life’s natural teachers, Hilda Cole, who taught generations of children to read and write and made it all seem like fun. And, oh, the wonderful smell of the corner cupboard full of plasticine, blunt scissors, raffia, beads and other delights, which came out after all the hard work had been finished – and the lovely round stove which gave out a tremendous heat and was surrounded by a circular guard to stop little hands getting burned. We won’t dwell on the outside lavatories, the girls off one playground and the boys off another, cold, miserable but necessary places.” Stoves as well as smells seem to loom large in memories of schooldays.

Figure 6.6 Miss Cole and the Class of 1935. The School DayThe school day began with assembly and prayers for the classes all together, occasionally being led by the Rector. The ringing of the school bell marked the sections of the school day and was a useful ‘timepiece’ for others working in the fields and houses around the village. The school was lit by oil lamps, and water from the pump at Mrs Clark’s cottage nearby was used for drinking purposes at the school. A popular duty among the pupils was to collect the water in the galvanized two-gallon water cans and place them on the windowsills, with the enamel mug provided. For a long time, the pump water from the school and ‘School House’ was considered unfit for drinking, because of the proximity of the churchyard; but, according to the Log Book, in May 1940 the water from the school pump was analysed and finally pronounced fit for drinking. Derrick Bladder, who was a pupil at the school from about 1927 to 1936, says, “We did the usual lessons, (the basic ‘three R’s’, History, Geography, Nature Study). We used to play sports and on a Friday afternoon we boys used to work on the vegetable patch. We loved going out instead of being in school, especially when the season was right. Happy days.” The children also enjoyed nature walks around the lanes and up to Wood Street and Ox Hill, walks still fondly remembered today. Evidently, Mr Woolley, in common with his predecessor, liked introducing the older pupils to scientific experiments. Mr Woolley taught the children gardening by maintaining a school garden in the field by the Rectory. Kenneth Woolley remembers plum trees, vegetables, flowerbeds, even rose arches and that “Dad was keen on his marrow beds; we collected leaves to make leaf mould”. The soil was heavy Worcestershire clay and all water had to be brought from the ‘School House’ by Mr Woolley. In the 1930s, the older children spent one day a week at Great Malvern School, where the boys were taught woodwork and the girls cookery. Some extra holidays are also recorded in the Log Book, such as those for Royal Weddings: the Duke of York’s (later to be George VI) in 1923; the Duke of Kent’s in 1934; and the Duke of Gloucester’s in 1935. On January 28th 1936, “the scholars and teachers attended the Parish Church for a Memorial Service” to mark the funeral of George V. Alf Young remembered that on Armistice Day, November 11th, the children would march to the War Memorial by the church gate. After Guarlford SchoolBefore the Second World War children either stayed at Guarlford School until they were fourteen or went to one of the Grammar or High Schools in Worcester, Hanley Castle or Tewkesbury at ten or eleven. The Secondary Modern Schools in Malvern (later state comprehensive schools) were not built until the 1950s. The Chase, now a College of Technology, opened in 1953, and Dyson Perrins C.of E. School in 1958. Those who stayed at Guarlford School until they were fourteen entered employment, for example on farms, as did Derrick Bladder and Lil Gilroy); or they became apprentices in local businesses, such as Phyl Bayliss’s needlework apprenticeship, while Alf Young was apprenticed as a carpenter to Thomas Powles (where the firm of ‘Walsh’ is now). WartimeVery little appears in the Log Book about the progress of the two World Wars outside the village. The girls, as well as the boys, helped with ‘war work’ in the First World War, and within a fortnight in August 1914 the Upper Standard Girls made thirty-nine shirts and six pairs of socks for the Army. There is a poignant reference to the school being closed to enable children to attend the funeral of a young man who had himself been a pupil just a few short years before. Several times the words “no coal, so no school” appear in the winter of 1917. Memories are, however, still clear about events in the parish in the Second World War. There is a description of how, before the Second World War, the ‘Gas Van’ came to the village, and Mr Woolley had to supervise the youngsters trying out their gas masks. They went into the van, where tear gas was turned on, to test if the masks were all right and being worn correctly. And Margaret recalls: “We had to walk down the lane with our gas masks in boxes. I remember sitting there and we had to try to see if we could breathe in. Some of the younger children had ‘Mickey Mouse’ masks and I was just too old to get one. I was quite upset.” Margaret also remembers that she and her friend were sent to the girls’ cloakroom to try to make shelters with the cardboard mats used for exercise: “If there was an explosion and the blast was blown in we would have used these mats to protect us. I don’t think they would have had much effect, but we thought it was quite funny at the time. We also had to knit things, socks for sailors and so on.” The children like Edwin and Margaret and others were very involved in salvage collections: “We had to bring stuff in for salvage; it was going to be judged who brought in the most valuable stuff. They divided us into four groups, one in each corner of the playground; we were in the same group as the children from The Rectory. Our Dad found an old motorbike that he had scrapped and thrown in the pit up at the house. So we dragged this old motorbike out, took it down to School and found that part of the engine was aluminium - they regarded that as valuable.” So Edwin and Margaret’s group won the prize! Guarlford School supplied many ex-pupils to the war effort: as Sam Beard says, “When World War Two came along, Guarlford School pupils were well to the fore and included one Wing Commander and two or three pilots (RAF) and two Warrant Officers (Royal Artillery)”, as well as other men, together with Land Army girls and Wrens. The main effect of war on the school was the arrival on November 29th 1940 of twenty-three evacuees from Selly Park School, Birmingham, with their teachers, Miss Gosling and Miss Morris. In 1939 the authorities had considered closing Guarlford School and transferring the children to Madresfield, as the building was deteriorating and also, by May, the numbers had dropped to fifty children between the ages of five and fourteen. This was partly a result of smaller families, but also the fact that, as mechanisation increased, there were fewer labourers working on the land and occupying the tied cottages. However, as the probability of war increased, it had been decided to keep the school open to welcome evacuees. Mr A R Rose was one of these evacuees and he described his memories of the village school: “I remember the ‘Brummy’ kids thought the country accent was a bit funny, no doubt the Guarlford kids thought our accent was funny too. We were not very scholastically inclined at the village school; we were more interested in the ferrets and things kept by the son of Mr Woolley, the schoolmaster, and the superb model planes made by his other son.” The Woolley Family

Figure 6.7 Mr and Mrs Woolley with, L to R, David, baby Peter, John and Monica, c.1923. John was the eldest of the six, born in Chard in 1915. After leaving Guarlford School, he went on to Worcester Grammar School and was a keen member of Guarlford Football Team and the Tennis Club. He worked in the Worcestershire Education Department until he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve before the outbreak of the Second World War. In 1916, David was also born in Chard. David, a keen cyclist, cricketer, tennis and bowls player, was a friend of Colin Bradshaw, brother of Joan. He had a private tutor at home and then trained as a pharmacist in Malvern and Taunton, being sponsored through college by a Taunton chemist. David served in the Army during the War. He finally owned three chemist’s shops and an optician’s in Bristol. Then came Monica, who was born in Crewkerne in 1918. Monica, who had been slightly disabled in childhood by infantile paralysis, went to Tewkesbury High School and became a teacher. Miss Monica Woolley was a familiar and popular figure to many in Malvern, as, after teaching firstly in Birmingham, she became temporary head of Hanley Swan School when war began, and finally taught for forty-two years at Malvern Parish School, also known as Mill Lane School. During the war, Monica was in charge of the evacuee children being sent to escape the ‘blitzing’ of Birmingham, and when she died in November, 2003, the Malvern Gazette tribute remembered her “kindness and truly dedicated teaching”. Next was Peter, born in Hallow in 1922. He went on to Hanley Castle Grammar and trained as an engineer, working at ‘Archdales’ in Worcester and then at the Royal Radar Establishment (RRE) in Malvern. After him came Kenneth, who was born in Guarlford in 1925, was educated at the Village School and then at Hanley Castle Grammar School. He joined the RAF in the Second World War and afterwards, like his father and sisters, he became a teacher, at Pershore Abbey Park Junior School, and finally retired as a deputy headmaster. He continued to fly in peacetime, enjoying his hobby of gliding. The youngest child, Margaret, who like Kenneth, has supplied many memories for this history, was born in the School House in 1929 and, after following her sister to Tewkesbury High School, taught in Dartmouth and Australia. In the photograph of Miss Coles class of 1935 (above), Margaret is the happy little girl standing front left, as she describes herself, “all knobbly knees and gappy smile”. The School House was not large, but was home to the family of six children and their parents. Margaret recalls, “The house was usually cold and damp. The tiny sitting-room, the ‘room’ as it was called, had a fireplace, but I only remember the fire being lit at Christmas. The bedrooms had small fireplaces, but you had to be near death before one was lit and then the smoke nearly finished you off! The only carpet in the house was in ‘the room’. Hall, kitchen and scullery were brick-floored and looked lovely when first washed. Runners of hardwearing material provided some protection, but little warmth. Linoleum covered the three bedroom floors as well as the stairs. Rag rugs were some small comfort beside beds.” Margaret described how the School House was always full of pets. At one time after the Second World War, there was even a monkey at the School House: “I came across him in a pet shop in Manchester. When he put out his little cold hand for me to hold and pleaded ‘Get me out of here’ I was hooked. Mother was always a sucker for animals and people in distress, so she gave permission for me to bring him home. Pete built a big cage in half of the brick-built henhouse in what were originally the boys’ toilets. Kim, as we called the monkey, had a heater and two boxes into which he could retire day or night. He had strong branches to climb, hens to pull faces at, and Mother who fed him grapes and bananas through the bars. They were great pals. In winter Kim could be found sitting on her knee before the fire, while in summer he played around her feet. When he had long out-lived his wild brothers and Mother could do no more for him, she called the vet. But Kim had beaten him to it. They found him curled up as though asleep in his night-compartment.”

Figure 6.8 Mr Woolley and the Class of 1935.

Kenneth says that the family had little spare money as such, but they were very happy. The children all had their ‘tasks’ to do in turn. Both Margaret and Kenneth remember having to fetch milk from the Medcalfs at New House Farm every afternoon or evening after school. For Kenneth, it was eerie coming back through the churchyard, expecting every minute that something would jump out from behind the yew trees lining the path. His father was earning just twenty pounds a month before the war but, as has been seen, ensured that his children had the best opportunities available. In those days, even if you won a scholarship, there were still expenses to be met. During the early years of the war, Mr Woolley himself was also an Air Raid Warden, “determined to do his bit”: he had a whistle and a rattle (in case of gas attacks), gas-mask and helmet, and when the sirens sounded, he would disappear for hours – the family didn’t know where. Tragically, in 1941, great sadness came to the happy family living at ‘School House’. John, the eldest son, who had been very involved in village life, had joined the RAF and his plane did not return from a mission on June 19th 1941. Then, just six months later, on December 12th, Mr Woolley died of kidney failure at the age of sixty-two. However, his influence and memory still live on in the many pupils who remember him today. He is buried in Guarlford churchyard. The family stayed on in the School House. Peter Woolley was very much the handyman around the house. After the war, the old range was removed and Peter built a brick fireplace. There must have been an earth closet next to the washhouse originally, because Margaret can remember the excitement when the flush toilet arrived and she can also remember helping Peter with building work: “The small brick building to the left of the gates was our garage. Ken had some electrical training and he rewired the house at some stage. People were resourceful then – they had to be.” Mrs Woolley purchased The School House in February 1951, living there until her death in 1971 at the age of 81. ClosureThe death of Mr Woolley brought a great change to Guarlford School. On 9th January 1942, nineteen Senior pupils (i.e., those aged eleven to fourteen) were transferred to Great Malvern Parochial School in Manby Road, which is now known as Malvern Parish School. This left two classes at Guarlford School in the care of Miss Cole and Miss Gosling, the latter becoming temporary Head of the school. School events continued to be recorded in the Log Book: for example, on 16th December 1942, “…a wireless receiving set was set up in the school”; and on 19th July 1944, “…the children were taken to the Church corner to watch King George VI and Queen Elizabeth pass by after their visit to Malvern”. By 15th August 1944, most of the evacuees had returned to Birmingham with their teacher, Miss Gosling, and Miss Cole was left as sole teacher. However, there had already been discussions in July 1944 at Madresfield about moving the Guarlford Junior children to Madresfield School, and the Madresfield Senior Elementary children to a school in Malvern Link, where they would receive a more appropriate education. Guarlford School is described in one Madresfield record as being without a Head Teacher and the school building in bad repair, something echoed in other documents of the time. One resident also recalls “…a large hole in the roof in the Infants Room. When it rained the water was collected in a big bath and older boys used to have to come and empty it. By 1943 the floor in the corner of the large room was rotting and had to be barricaded off.” Eventually, it was agreed that, as there was to be a new Church of England Senior School in Malvern Link and the school-leaving age was to be raised to fifteen in 1945, it would indeed be better for the Madresfield Seniors to move and the Guarlford Juniors to take their place. So, on 2nd October 1944, sixteen children from Guarlford, between the ages of seven and eleven years of age, were entered onto the Register at Madresfield School, among them three evacuees who later returned to Birmingham. Other pupils, having reached the age of eleven plus, moved on to Secondary education elsewhere, leaving just fourteen Infants at Guarlford School in the sole care of Miss Cole. It was at this time that a school bus began to run from various parts of the parish and then via Chance Lane to Madresfield and back, something, which continued almost to the end of the twentieth century. The influx of Guarlford children also provoked discussion about the provision of school dinners at Madresfield, as they could “…not be expected to go home for their dinner” and eventually a kitchen was provided. The Guarlford School Log Book ends on January 16th 1946, but nowhere is there any record of exactly when Guarlford National School closed. The Madresfield School Register records the fact that, on 2nd April 1946, ten children from Guarlford, between the ages of five and seven years, were enrolled at Madresfield. Money raised by the sale of Guarlford School was used to improve the facilities at Madresfield and Miss Cole rejoined her pupils when she was interviewed in November 1946, and appointed as an assistant teacher at Madresfield School; she later married Mr Wall of Madresfield. Many children from the parish still attend Madresfield Church of England Primary School, as Guarlford is in its catchment area; but no longer do they wait for the school bus in lanes and by the church, picking up conkers on autumn mornings as their forebears did. Guarlford School and ‘School House’ have gone, demolished in the early 1970s, and two semi-detached houses have been erected on the spot where many still in the area today spent their childhood; but the memories remain, for, as Sam Beard simply but eloquently says: “Guarlford was their starting point and they could not have wished for better”. From 'The Guarlford Story', copyright the Guarlford History Group 2005; revised and updated 2015. Last updated 3rd March 2015 |

As

Mr and Mrs Woolley lived in ‘The School House’, they and their

family were prominent in the life of the village. Mrs Lucy Margerie

Woolley trained as a nurse in the Manchester area before marrying in

1914 and, after bringing up her children, she practised privately in

Malvern. Margaret Llewelyn (nee Woolley), the youngest of the six

children says, “My father was a good, hard-working man and

conscientious teacher. For fourteen years he was also a Captain in

the Church Army, serving in Cromer, Plymouth, Eccles and Chard,

before moving to Hallow and Guarlford. To us he was a loving father

and devoted husband.”

As

Mr and Mrs Woolley lived in ‘The School House’, they and their

family were prominent in the life of the village. Mrs Lucy Margerie

Woolley trained as a nurse in the Manchester area before marrying in

1914 and, after bringing up her children, she practised privately in

Malvern. Margaret Llewelyn (nee Woolley), the youngest of the six

children says, “My father was a good, hard-working man and

conscientious teacher. For fourteen years he was also a Captain in

the Church Army, serving in Cromer, Plymouth, Eccles and Chard,

before moving to Hallow and Guarlford. To us he was a loving father

and devoted husband.”